“As my sufferings mounted I soon realised that there were two ways in which I could respond to my situation — either to react with bitterness or seek to transform the suffering into a creative force. I decided to follow the latter course.”

― Martin Luther King Jr.

If you are unhappy about any regulatory decision made by the Police Pension Authority (PPA) concerning an injury award or ill health retirement you are able to appeal against the decision. (In most forces the PPA is an office vested in the sole personage of the Chief Constable)

The intention of this post is to remind our readers of some of the ways injustice can be resolved. As with other legal challenges, an appeal needs to be based on some good reason. Therefore, you will need to be able to point to any apparent error of fact or law which the authority has made.

A PPA carries ultimate responsibility, and will be the body named in the appeal, but the actual decision in question may have been made under delegation by a HR person, some other civilian worker or a SMP. A SMP has a regulatory duty to make certain decisions on behalf of the PPA. Decisions made by a Police Medical Appeal Board (PMAB) can also be subject to appeal.

The avenues of appeal available depend on the Regulation the decision was made under and whether you are currently serving or medically retired. Any decision which you receive from the PPA, SMP or a PMAB will be set out in writing and will normally contain the rationale or reason for the decision. A decision notification should also outline the reasons for the decision, and list avenues through which you may appeal the decision, as well as the relevant time limits within which an appeal must be made.

As well as formal avenues of appeal it is worth bearing in mind that complaints can be made about any individual employed by a police force, or against the police force itself. Complaints are justified wherever there is incompetence, injustice or a refusal to act within the rules of the pension schemes. All forces are required to have a formal Internal Disputes Resolution Procedure (IDRP) and will provide you with details of how it is operated.

Complaints about alleged criminal acts can be made to the Independent Police And Crime Commissioner.

Complaints to governing bodies (e.g. the General Medical Council or the Law Society) about the behaviour of the decision maker can also be pursued either unilaterally or combination to an Ombudsman concerning further maladministration.

Here is a brief list of the more usual avenues for appeal.

- Regulation 32 Reconsideration (Further reference to medical authority – PIBR 2006)

- Police Medical Appeals Board (Regulation 31 PIBR 2006 – Appeal to board of medical referees)

- Crown Court

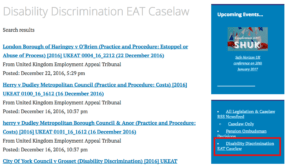

- Employment Tribunal & Employment Appeal Tribunal

- Pension Ombudsman

- Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman

- Equality and Human Rights Commission

- Equality Advisory and Support Service

- Judicial Review

Regulation 32

Of particular note, as being probably the most useful, yet most under-used mechanism for having questionable decisions corrected is contained in regulation 32 of The Police (Injury Benefit) Regulations 2006. This is a very important provision of the Regulations, which every serving and retired officer who seeks or who is in receipt of an injury award should make themselves, their Federation Rep and any legal representative familiar with. Here it is in full:

Further reference to medical authority

32.—(1) A court hearing an appeal under regulation 34 or a tribunal hearing an appeal under regulation 35 may, if they consider that the evidence before the medical authority who has given the final decision was inaccurate or inadequate, refer the decision of that authority to him, or as the case may be it, for reconsideration in the light of such facts as the court or tribunal may direct, and the medical authority shall accordingly reconsider his, or as the case may be its, decision and, if necessary, issue a fresh report which, subject to any further reconsideration under this paragraph, shall be final.

(2) The police [pension] authority and the claimant may, by agreement, refer any final decision of a medical authority who has given such a decision to him, or as the case may be it, for reconsideration, and he, or as the case may be it, shall accordingly reconsider his, or as the case may be its, decision and, if necessary, issue a fresh report, which, subject to any further reconsideration under this paragraph or paragraph (1) or an appeal, where the claimant requests that an appeal of which he has given notice (before referral of the decision under this paragraph) be notified to the Secretary of State, under regulation 31, shall be final.

(3) If a court or tribunal decide, or a claimant and the police [pension] authority agree, to refer a decision to the medical authority for reconsideration under this regulation and that medical authority is unable or unwilling to act, the decision may be referred to a duly qualified medical practitioner or board of medical practitioners selected by the court or tribunal or, as the case may be, agreed upon by the claimant and the police authority, and his, or as the case may be its, decision shall have effect as if it were that of the medical authority who gave the decision which is to be reconsidered.’

(4) In this regulation a medical authority who has given a final decision means the selected medical practitioner, if the time for appeal from his decision has expired without an appeal to a board of medical referees being made, or if, following a notice of appeal to the police [pension] authority, the police [pension] authority have not yet notified the Secretary of State of the appeal, and the board of medical referees, if there has been such an appeal.

The decision maker, which can be either the SMP, or a PMAB, is asked to look again at (reconsider) the decision, in the light of argument and/or information presented by the individual subject to the decision. It provides a simple way of having a mistake corrected.

Mr Justice King in the Haworth judicial review stated that [Regulation 32 is a]

‘. . . free standing mechanism as part of the system of checks and balances in the regulations to ensure that the pension award, either by way of an initial award or on a review to the former police officer by either the SMP or PMAB, has been determined in accordance with the regulations and that the retired officer is being paid the sum to which he is entitled under the regulations.’

Anyone considering using regulation 32 should note well that there is no time limit on when it can be used. It can be activated at any time following a decision – even many years later. We know of instances where historic maladministration has been discovered by pensioners, who can then use regulation 32 to have matters corrected. A typical instance is where an incorrect degree of disablement has been decided.

It is, however, well worth requesting a reconsideration of a decision at the same time as giving notice of appeal to a PMAB. That way, you secure registration of the PMAB appeal within the time limit, which allows the PPA to correct matters swiftly, thus negating the need to go to a PMAB. This has mutual benefits to both the individual and the PPA as stress and cost can be minimised.

One further valuable aspect of this regulation is that if the original decision maker is ‘unable or unwilling’ to make the reconsideration (a SMP might have retired, died, or simply not wish to be proved wrong) then individual is granted an extraordinary power. The individual and the PPA need to agree over selection of the alternate ‘duly qualified medical practitioner’ who will make the reconsideration. That means the individual can object to any doctor proposed by the PPA (on reasonable grounds, such as suspicion of bias or lack of appropriate qualifications). More importantly, though still untested in the Courts, it seems that the individual has the right to propose a duly qualified medical practitioner of his or her own choosing – and that doctor need not be someone who is already acting in the role of SMP for any force.

PMAB

A Police Medical Appeal Board is the method of appeal stipulated in the Regulations as an appeal to board of medical referees when person is dissatisfied with the decision of the selected medical practitioner as set out in a report under Regulation 30(6). A PMAB usually consists of a panel of three (two occupation health doctors and a specialist in the condition being assessed). Notice of intention to appeal to a PMAB needs to be given to a PPA within 28 days of receipt of formal notification of a decision. The appellant then has a further 28 days in which to provide the PPA with the full grounds for the appeal. (There is discretion for these time limits to be extended, within reason.)

A police pension authority does not have the right to appeal to a PMAB and therefore must take a SMPs decision it contests to judicial review.

Crown Court

If a serving officer simultaneously applies for an injury award/ill-health retirement and the police pension authority fails or refuses to refer the decision to a SMP, or a decision of the police authority is that the officers refusal to accept medical treatment is unreasonable, then the refusal or the suggested treatment can be challenged in a Crown Court.

Employment Tribunals

Employment Tribunals are responsible for hearing claims from people who think someone such as an employer or potential employer has treated them unlawfully (unfair dismissal, discrimination, unfair deductions from pay) . Employment Appeal Tribunals are responsible for handling appeals against decisions made by the Employment Tribunal where a legal mistake may have been made in the case.

Post-termination victimisation or discrimination claims are justiciable under the Equality Act 2010 following the recent Court of Appeal Judgments in Jessemy v Rowstock Ltd and Anor [2014] and in Onu v Akwiwu & Anor [2014]

In both decisions Court of Appeal decided that the Equality Act 2010 should be read to cover post-employment victimisation. This should clear up the uncertainty caused by conflicting Employment Appeal Tribunal decisions on this issue. In other words, a ‘post-employment‘ medically retired officer has the right to bring a disability, age or gender discrimination claim to an employment tribunal.

Pension Ombudsman

The Pension Ombudsman (PO) has legal powers to settle complaints, maladministration and disputes. In recent years the PO has played an important part in having maladministration of injury awards corrected. If the PO decides someone responsible for a decision or the wrongful exercise of a power of discretion, or has got the law wrong or has not followed the scheme’s rules or regulations, or not taken the right things into account, they can tell them to go through the process again, but properly.

If financial loss has occurred, the PO can enforce the decision maker to put the disadvantaged individual back into the position they would have been in if everything had been done correctly. The PO can also decide upon redress for non-financial injustice, whether someone has been caused significant inconvenience, disappointment or distress. Although amounts of compensation are usually rather low, they serve to underline the finding of wrongdoing.

Every pension scheme has to have an Internal Dispute Resolution Procedure (IDRP) system built in to enable members of that scheme to complain about matters concerning the administration of their pension (section 50 of the Pensions Act 1995). Injury awards are no exception.

An IDRP can be a one or two part process. One part may settle the matter, but if not on it goes to part two. Be very aware though that the ‘I’ in IDRP does not stand for Independent. In part one a senior person is asked to consider your submission. If there is no resolution, then someone else is appointed to take a look. That person may be another force employee, or, more often will be someone with no close connection to the force who is deemed to have some relevant expertise. We have no data on how many IDRPs produce an acceptable solution at either stage. The process can take several months. If a solution isn’t found or the IDRP process is ignored, then it can go to thePensions Ombudsman’s office for adjudication.

But if you don’t initiate an IDRP you will find that the Pensions Ombudsman – who is the person who can really do something about maladministration – will not be able to accept your complaint. He likes to see himself as a mediator, a settler of differences, and an arbiter of the law. He wants to see the parties to a dispute make efforts to resolve it before he is asked to get involved.

Quite often the failure of the PPA to correctly deal with the IDRP stages adds to strength of evidence that maladministration has occurred.

Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman

The Parliamentary and Health Service Ombudsman provides a service to the public by undertaking independent investigations into complaints that government departments, the National Health Service in England and a range of other public bodies in the UK have not acted properly or fairly, or have provided a poor service.

At this time complaints are raised through a person’s MP. Soon the service will be open to take complaints directly.

This real case story neatly summarises what this ombudsman can do:

. What happened to Mr R was an example of disability discrimination and serves a good example of the Ombudsman providing redress for the individual – and also recommending systemic improvements for a wider public benefit. It is a synonym of how some SMPs treat those disabled people forced in front of them.

An important point regarding his ombudsman is that complaints about the exercise of clinical judgement are within its jurisdiction.

Equality and Human Rights Commission & Equality Advisory and Support Service

The Commission has responsibility for the promotion and enforcement of equality and non-discrimination laws in England, Scotland and Wales. It took over the responsibilities of three former commissions: the Commission for Racial Equality, the Equal Opportunities Commission (which dealt with gender equality) and the Disability Rights Commission.

The EHRC’s functions do not extend to Northern Ireland, where there is a separate Equality Commission (ECNI) and a Human Rights Commission (NIHRC), both established under the terms of the Belfast Agreement.

The Equality Advisory and Support Service (EASS) is an advice service. It is aimed at individuals who need expert information, advice and support on discrimination and human rights issues and the applicable law, particularly when this is more than other advice agencies and local organisations can provide.

Judicial review

Judicial review is an audit of the legality of decision-making by public bodies. Judicial review may be used where there is no right of appeal or where all avenues of appeal have been exhausted

- when a decision-maker misdirects itself in law, exercises a power wrongly, or improperly purports to exercise a power that it does not have

- a decision may be challenged as unreasonable if it “is so unreasonable that no reasonable authority could ever have come to it”

- failure to observe statutory procedures or natural justice

- when a public body is, by its own statements or acts, required to respond in a particular way but fails to do so.

A JR is a remedy of last resort. However, the Court has a wide discretion to hear cases even if there is an alternative appeal mechanism available in line with M and G v IAT 2004. They successfully argued that the statutory appeal was both procedurally and substantively inadequate to safeguard the rights of asylum seekers.

Applications for JR will be refused are those where there are proceedings in another forum already underway or imminent.

We hope this brief guide to routes of appeal will serve to inform and encourage all serving, about to be retired and retired officers who believe they have suffered at the hands of the widespread incompetence and ignorance of the Regulations, so frequently displayed by those in authority over their ill health and injury pensions, to stand up and challenge decisions which they believe are wrong.

This is not intended to be a comprehensive guide to how to appeal. In all cases, you should seek professional advice and assistance before initiating any avenue of appeal or challenge. IODPA can, and will, give initial advice and information, and in some areas the Federation will be knowledgeable and helpful. IODPA retains excellent solicitors who can be instructed by individuals, and funding for them can be obtained via the Federation.

Latest Blog Comments