Access to Medical Reports Act

“If you are distressed by anything external, the pain is not due to the thing itself, but to your estimate of it; and this you have the power to revoke at any moment.”Marcus Aurelius, Meditations

Here is an unsettling fact. It seems that most police force are aware of the Access To Medical Reports Act, but some chose not to comply with it.

The Access to Medical Reports Act 1988 (AMR Act) provides the right for people who have been medically assessed for insurance or employment purposes to withhold their consent for access to medical records, and also to see any report produced by the commissioned doctor before it is sent to the person or organisation who commissioned it.

This Act applies directly to the process of review of police injury pensions, as an injury award is a form of compensation (i.e. insurance) for injury on duty.

- On review of an award, it gives the right to demand changes and if you are still unhappy with the report, you have the right to stop it being sent to the police pension authority.

- On an application for an award, you can demand corrections to medical inaccuracies (diagnosis, apportionment or causation) made by the SMP and if you are still unhappy with the report, you have the right to have your objections added to the report or to stop it being sent to the police pension authority. Stopping disclosure of the report may mean your application is not continued any further.

Here are extracts from two recently used consent forms, issued to IOD pensioners by two different forces, demanding agreement that the medical authority’s report shall go direct (or after a benevolent pause of three days!) to the Human Resource department:

From Avon and Somerset Constabulary:

And from Northumbria Police:

The forces who put out these manipulative psuedo-requests for consent will know all too well that there is legislation concerning the ‘provision of reports’. Why otherwise would they ask for ‘consent’ to release? That said, everything is wrong about the demands asked of the signatory. Both of these consent forms have but two options, each option which, with brazen shamelessness, breaches the Access to Medical Reports Act.

It is in fact illegal to release the report simultaneously to both the recipient and the third party, in this case the police pension authority. It is also unlawful to demand a three ‘working day’ window to inspect the report.

Where a person is induced to enter into giving consent entirely or partly by a false assertion, such as not being truthful with the rights gifted to them by legislation and failing to provide understanding in broad terms the nature and purpose of the disclosure and the rights they have, then any misrepresentation of these elements will invalidate consent.

The insistence that the report cannot be changed is also contrary to the Access to Medical Reports Act. Nowhere is the signatory explained their full rights. The reason for this is clear – it is a plain attempt to blitzkrieg disabled former officers to ensure they yield to the will of the pension scheme manager; to force compliance with a bullying, superior force.

The AMR Act makes it crystal clear that consent to any report being released can be withdrawn without retribution. If an individual being assessed is unhappy with any element of the report, and says so, then it is illegal for the doctor to release it to any third party, including the police pension authority. In real-terms this means the review is over… stalemate.

Forces know this. We can only conclude that is why there is no mention of the Act in the consent form and that is why your rights are not explained. Why give you an informed consent form when they can con you into forced acquiescence by saying you have 72 hours and the clock starts … now!

The basic points of the AMR Act can be summarised thus:

- Section 3 of the Access to Medical Reports Act states that the person has to give his or her consent for their employer to be given access to their medical records.

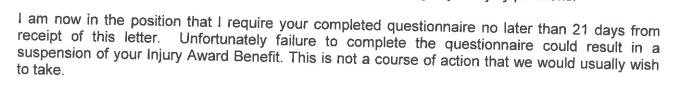

- Section 4 of the Act the doctor or medical practitioner must wait 21 days before sending the report to the employer.

- An employer must obtain the person’s written consent which must then be provided to the doctor in order to be provided with access to the requisite report.

- Under Section 5 of the Act a person can request the doctor to amend the report if they feel that it is incorrect or misleading.

- An employee is entitled to withhold their consent for a report to be provided to an employer having been provided access to it under Section 4 of the Act.

- Section 6 of the Act states that doctors will retain all reports requested by employers for six months

At this point we have to mention that the Police (Injury Benefit) Regulations 2006 require a police pension authority ‘refer for decision to a duly qualified medical practitioner selected by them . . . ‘ the relevant questions. At review, the relevant question is degree of disablement. Specifically whether there has been any alteration in degree of disablement. The Regulations also require,

30-(6) The decision of the selected medical practitioner on the question or questions referred to him under this regulation shall be expressed in the form of a report and shall, subject to regulations 31 and 32, be final.

30-(7) A copy of any such report shall be supplied to the person who is the subject of that report.

We can see, therefore, that the decision of the SMP must be in the form of a report. The SMP can not inform the police pension authority of his decision in any other way. So, no sneaky way round the Regulations or the AMR Act.

What happens if the doctor decides to release the report anyway? Firstly they breach the Access to Medical Reports Act and a court order can be easily obtained to enforce the Act. In effect this will nullify the report and any decision based upon it. Secondly, the GMC will almost certainly punish the doctor for committing gross misconduct. In all likelihood the doctor will be struck off.

Further, there will also have been a concurrent breach of the Data Protection Act.

As things stand in the strange alternative legal world view of Avon and Somerset and Northumbria, pensioners are being instructed to sign the consent form without seeing the report – in this case before they have even allowed access to their medical records. This is in no way seeking ‘informed’ consent. It is patently ridiculous to expect anyone to sign consent for the SMP to send in a report that has not yet been written, and has not been yet seen by the individual concerned.

The concept of consent arises from the ethical principle of patient autonomy and basic human rights. You can not consent to release of a report that, at that time, is yet to come into being.

Informed consent must be preceded by disclosure of sufficient information – in relation to a medical report, the report has to be visible for consent to be formed. Consent can be challenged on the ground that adequate information has not been revealed to enable the patient to take a proper and knowledgeable decision.

Tellingly, in the police consent form, there is no mention at all of any of the rights provided under the Access to Medical Reports Act 1988 – there is no mention in the consent form of the Act itself.

The General Medical Council (GMC), the British Medical Association (BMA), and the Faculty of Occupational Medicine (FOM) have issued guidance on the law governing commissioned reports. They recognise there are protocols enshrined in law, and the guidance is a consequence of that law.

The Faculty of Occupational Medicine makes it clear in this document titled General medical council guidance on confidentiality (2009) and Occupational Physicians that it’s members have to comply with the guidance and ethics laid down by the GMC.

As quoted from this report, the GMC guidance –that confidentiality is a fundamental duty for all doctors and must not be breached without the consent of the individual concerned – strengthens the notion of “no surprises”:

… in the relationship between doctors and patients and because of cases reported to them where the content of a medical report deviated significantly from the patient’s understanding of what it would say.

In 2008 the FOM set their greatest minds to the task of examining whether Occupational Health doctors have to comply with the AMR Act.

An expert group was formed by FOM and this panel was chaired by Professor K Holland Elliott FFOM CMIOSH Barrister (non-practising). The result was a published report titled “Guidance for Occupational Physicians on compliance with the Access to Medical Reports Act” .

The main reason objective of the expert group was to to “explain the legal basis of our practice and how this differs from mainstream medicine in relation to this Act”.

The default recommendation of the expert panel was that if the occupational health clinician is “responsible for the clinical care” of the patient then the Act applies at all times.

An important conclusion of the report was that if the occupational health clinician bases a report from medical notes obtained from a GP, hospital or consultant then the Act applies.

In paragraph 62, the group come across the Rubicon that is the question of consent – the barrier which no SMP or HR Department may cross without falling foul of the law: “The Act sets no limit on the time the individual may take to consent to the release of the report and so it may potentially be delayed indefinitely“.

The specific wording of that Act that they are referring to is this:

Where an individual has been given access to a report under section 4 above the report shall not be supplied in response to the application in question unless the individual has notified the medical practitioner that he consents to its being so supplied.

Pay close to attention to the highlighted text. Consent can only be given once the individual has been given access to the report.

They concluded that they strongly agreed that, “An individual has a right of access to the medical report produced by the occupational health practitioner”.

Also they strongly agreed with the statement that, “When an occupational health physician writes a report based upon medical records supplied by the GP or hospital, the occupational health physician needs consent to send the report”.

Dr Bulpitt of Avon & Somerset clearly understands the implications. He said himself that if consent to disclose the report is withdrawn then,“we are in danger of the whole thing grinding to a halt”.

Remember that this isn’t the consent to obtain medical records in the first instance. As we’ve mentioned, the consent concerning disclosure cannot cover the consent to release a report that is yet to exist.

Are you an employee of a police ‘inhuman remains’ (HR) department that still thinks that the Access To Medical Reports Act 1988 doesn’t apply to police injury awards?

Let us put your doubts to bed once and for all. The British Medical Association (BMA) has a document titled “The Occupational Physician“. It was authored by the BMA occupational medicine committee.

Chapter 11 Access to Medical Reports Act 1988

How the Act affects occupational physicians

Although the Act, for most practical purposes, applies to reports provided by an individual’s GP or hospital doctor, it also affects occupational physicians in the following circumstances:

- where an occupational physician provides clinical care to the employee (care is defined in the Act as including examination, investigation or diagnosis for the purposes of, or in connection with, any form of medical treatment)

- where an occupational physician has previously provided medical treatment or advice to an employee (in the context of a doctor/patient relationship) and therefore holds confidential information which could influence the subsequent report

- where an occupational physician acts as an employer’s agent, seeking clinical information from an individual’s GP or consultant. In this case the occupational physician, acting for the employer, should seek the employee’s consent to request a report and explain his/ her rights under the Act.

Often the occupational health record of a former police officer contains confidential information where the force medical officer has provided treatment or advice in attempt to get that person back to work – so this is (b) and is covered by the AMR Act. Advice and/or treatment to get someone operational again should be the raison d’être of a police occupational health unit.

A report produced by an organisation’s own occupational health practitioner (or delegated agent) is covered by the AMR Act when the practitioner or predecessor has been involved in the employee’s treatment, even past treatment unrelated to the employee’s current medical condition. How many serving, but injured, police officers prior to retirement were sent for MRI scans? Counselling? Private operations to speed recovery? Referrals to rehabilitation centres? This all amounts to clinical care.

The guidance from the GMC, BMA and FOM all coalesces into the single agreement that if a report is based from clinical information gained from the individual’s GP then this is (c), above, and is covered by the AMR Act.

Diana Kloss QC of St John’s Buildings Barristers’ Chambers published an article in the Occupational Medicine Journal (September 1st 2016) that covers this exact subject. She touches upon the frustration felt by force medical officers such as Dr Bulpitt when she writes:

human resources and occupational health (OH) professionals are unhappy with the current guidance (under review) from the General Medical Council (GMC) that an OH report to management should be shown to the patient before it is sent and that they should be permitted at that stage to withdraw consent

She concludes that:

only when the employee is told what is in the OH report can he give valid consent to its disclosure to his employer…

Therefore, just as an employee can withdraw consent to disclosure of a GP report when he sees it (under the AMRA), so he can refuse to permit an [Occupational Physician] to send a report to management when he knows what it contains.

Somewhat playing to the intended audience of the journal, the QC mentions circumstances concerning the application of an ill health retirement in her article and makes a point that it is:

it is arguable that an [Occupational Physician] appointed to advise on an ill-health retirement pension may be considered to be in a position analogous to that of an expert witness especially when pension procedure is laid down in statutory regulations

But that argument has no relation to any medical report written from clinical information from an individual’s GP or consultant. In any case, Diane Kloss herself makes it clear that even an expert witness can have consent to their report withdrawn. In Kapadia v London Borough Of Lambeth [1999] Dr Grime, a Registrar in the Department of Occupational Health and Safety at King’s College, refused to hand over his report on Mr Kapadia – that he undertook on the instructions of Lambeth – to the Borough’s counsel on the first morning of the hearing as no consent to do so was provided by Mr Kapadia.

In relation to police injury awards, such a medical report required by the Regulations is not written by an ‘expert witness‘, they are written by a suitably qualified medical practitioner – under the full jurisdiction of the GMC, FOM, BMA and AMR Act. The applicant for an ill-heath retirement that withdraws disclosure just will be unable to prove to the police pension authority their entitlement to an injury award. The ability to exercise consent can not be denied.

A review under Regulation 37 is also commenced with a demand for full access to all medical records held by the GP practice. Notwithstanding the lack of any legal authority within the Regulations for asking for such information, any attempt to write a medical report on somebody without giving that person their statutory rights is scandalous.

And, if you’re wondering, why the distinction under the AMR Act between an occupational health doctor, not being a doctor responsible for the clinical care of the IOD pensioner, who writes a report from occupational notes, contrasted with the same doctor writing a report from medical information gleamed direct from GP and/or hospital notes? The former is not compelled to comply with the AMR Act whereas the latter is under the remit of the AMR Act.

The answer shows the foresight of the legislators that penned the AMR Act.

No one in the UK is registered with a GP – they are registered with a GP practice. There might a favourite GP there who you would prefer to see, or that nice doctor you saw since childhood may have recently retired. You may have moved home recently and changed GP practices. The GP practice may have amalgamated with a bigger, slicker more modern outfit.

The point is that a report written by a GP you have never met, from your comprehensive medical notes, who works at a GP practice which is responsible for your clinical care is no different from an occupational health clinician, who you don’t know, writing a similar report from the same medical files.

Neither ‘know you’, neither ‘have treated you’. But the locum doctor working at an understaffed GP practice (a locum is a doctor who stands in temporarily for another doctor) that is tasked with the request from an insurer or employer to provide a medical report is put in exactly the same position as the selected medical practitioner: a position whereby they must comply with the AMR Act.

This is why all reports based from medical records have to comply with the AMR Act. And this is why you aren’t told of your rights. People like Dr Bulpitt would prefer you not to know this.

Failure to properly advise IOD pensioners about the application of the AMR Act is a further deliberate misuse of the authority of a policing body. The insidious and creeping behaviour of some public officials employed by the police undermining the rights of disabled former officer is stark. The maladministration of injury awards is epidemic.

Until police bodies are held to account for deliberately attacking or neglecting legislation that have been set up to help protect our rights, the abuse will continue.

IODPA will always work to put an end to it. If you have been to see a SMP and are not happy with the report (or felt the SMP performed a blatant and partisan interrogation), why not remove consent for that report to be released. Be clear that the doctor’s licence to practice is at stake if he or she fails to comply.

Do not be browbeaten into compliance by threats of the legal services department that you have not complied. Regulation 33 of the Police Injury Benefits Regulations only compels a medical examination and/or interview if the police pension authority has considered whether there may be a change in the pensioners degree of disablement, a suitable interval has taken place, and has decided there is enough evidence of that being the case to pass the question of a substantial change, for decision, to the medical authority (negligent or wilful failure to attend said examination only permits a decision being made on the available evidence, attending satisfies this condition – subsequently withdrawing consent is a statutory right and is something else entirely).

You have control over who sees the report. It is in your power to decide that no-one should see it.

Until you see a consent form such as this fully AMR Act compliant suggested example that we have created and the full AMR Act statutory framework explained separately, explain to your force very clearly that you will not tolerate your rights being trampled upon:

| This is a guide to your principal rights under the Access to Medical Reports Act, which is concerned with certain reports provided for employment or insurance purposes. Your full statutory rights shall be provided in a separate document. Potentially the occupational selected medical practitioner may have access to your patient record. As a report, based upon medical records supplied by the GP or hospital, is being sought from the occupational selected medical practitioner and an evidence based judgement is asked for, then the Act applies even though the practitioner isn’t directly responsible for your clinical care. This follows Faculty of Occupational Medicine guidance. In line with GMC code of practice, you are a patient of the practitioner even though there is no traditional therapeutic relationship. |

| OPTION A

You wish to see the report before it is issued. The Selected Medical Practitioner will be informed and will not supply the report until you have seen and approved it. If the Medical Practitioner has not heard from you in 21 days, he will assume you approve and provide the report. When you see the report, if there is anything which you consider incorrect or misleading, you can request in writing that the Selected Medical Practitioner amends the report, but he may not agree to do so. In this situation you can:

|

| OPTION B

You can withhold your consent to a report being provided. |

Latest Blog Comments